Prologue

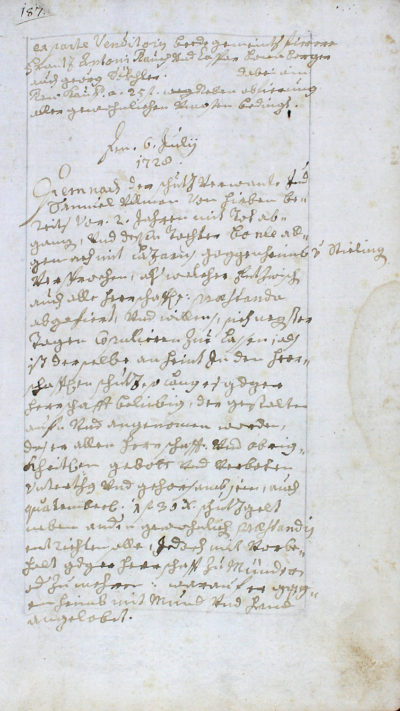

Entry in the Hürben (Bavarian Swabia) municipal protocols, dated July 6, 1728:

¶ 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0

Figure 1. Hürben Protocol;

STAA, VÖ Lit. 263 fol. 187 – July 6 1728

Figure 1. Hürben Protocol;

STAA, VÖ Lit. 263 fol. 187 – July 6 1728

Considering that the protected Jew Samuel Ullman of Hürben has been dead for two years, and his daughter Bonle is engaged to Lazarus Goggenheimb of Stieling (Stühlingen), the latter has meanwhile fulfilled all official requirements and is prepared to get married promptly and will be taken under protection as of today at the dominion’s discretion, on the condition that he shall humbly obey all official decrees and prohibitions and contribute his quarterly protection tax of 1 florin, 30 kreuzer, or as the dominion sees fit; thus confirmed by solemn oath.1

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 This record of Lazarus Goggenheimb, alias Siessel or Süssel, had remained the earliest trace of my maternal grandmother’s ancestors for many years. Siessel became the progenitor of a huge clan with descendants in Europe, the Americas, Australia, and the Middle East. But a question kept nagging me: Why would a young man in the early eighteenth century seek a wife some two hundred kilometres from home?

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 I was unable to find an authoritative work on the history of the Jews in Stühlingen, a German town at the foot of the Black Forest, bordering Switzerland. They had vanished after 1743. Although the Jews of Stühlingen form part of the foundation myths of the old Jewish communities in Gailingen, Tiengen, Endingen, and Lengnau – the root stock of Swiss Jewry – no bard has sung their dirge; no scholar has unearthed their secrets. The life and demise of the Stühlingen Jews from 1600 to 1743 seem to have transpired largely in a blind spot of history. The historical literature covering these circumstances and events is amazingly scant, both from an internal, Jewish and an external, gentile perspective. This gaping void begged to be filled. To learn more, I had to research it myself. But living in Canada, far from Stühlingen itself and the relevant archives, posed one difficulty, and not being a professional historian another.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 To approach the problem, I oriented myself on the method Shlomo Ettlinger had employed in his “Ele Toldot” inventory of the inhabitants of the Frankfurt ghetto in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.2 Though the scope of my problem was infinitesimally smaller than Ettlinger’s, I would be using potent tools powered by technology and passion, and the most precious, but frequently squandered, resource: time – time unencumbered by meetings, deadlines, or other people’s priorities.

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 A pilot study based on limited existing primary data, together with some newer transcriptions of eighteenth century county and municipal accounting books, enabled me to develop a technique for systematically exploiting the patterns found in time, names, and locations to construct a pixelated model of the historical community. This early work was implemented on a giant spreadsheet.

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 I then found a researcher in southern Germany who was willing to travel to the county archives in Donaueschingen and to their provincial equivalent in Karlsruhe on a contractual basis, both for me and later on also for another interested party. Our researcher extracted dated abstracts of each entry concerning Stühlingen Jews in municipal, judiciary, and county records between 1600 and 1745. But as more and more archival transcripts started to arrive, the spreadsheet technique turned progressively impractical. It became necessary to write extensive analysis software based on a relational database. The original narrative listings were fragmented, filtered, transformed, sorted, interpreted, and reassembled.

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 Gradually a picture started to emerge from the mist, a picture of real people with their fortes and foibles, their occupations and relationships. Little by little, individuals coalesced into an evolving community. The Jews of Stühlingen multiplied, spread, and were finally expelled. From some 300 typed pages systematically listing abstracts drawn from 205 individual sources of dry, administrative prose, broken down into 4826 primary, dated records that refer to 190 distinct individuals who are named a total of 7538 times, it became possible to reconstruct the likeness of a long-forgotten community – a likeness no less fascinating than that of a delicate vase lovingly restored by an archaeologist, shard by shard from a pile of rubble.

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0

1StAA. VÖ 263 fol.187. Author’s translation.

2Ettlinger, “Ele Toldot.”

Comments

0 Comments on the whole Page

Login to leave a comment on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 7

0 Comments on paragraph 8

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 8

0 Comments on paragraph 9

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 9

0 Comments on paragraph 10

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 10

0 Comments on paragraph 11

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 11

0 Comments on paragraph 12

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 12