2-6

¶ 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0

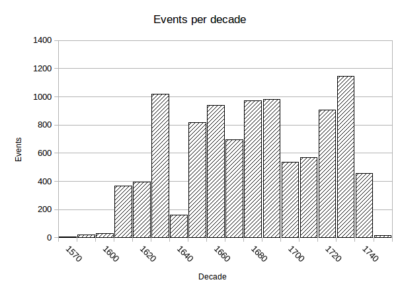

Figure 3. Number of Records per Decade

Figure 3. Number of Records per Decade

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 The process yielded 4826 dated records, extracted from 209 source documents and broken down further into 10,040 individual events, that is, dated items linked to a specific moniker. Events do not cover the period from 1600 to 1750 evenly (see fig. 3).

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 Undoubtedly, many of the event attributions to specific persons are incorrect, and 22% of events lacking an attribution is disappointing. With a massive expenditure of effort it should be possible to improve these deficiencies. But is it worth it? It might provide us with a few more interesting details, but it is unlikely to change the overall picture.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 Unfortunately, primary sources mentioned males almost exclusively. Nevertheless, it was possible to identify some 46 wives and daughters either by name or at least by that of both husband and father.

¶ 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0

Despite the large number of events processed, a final yield of 190 identified men and 46 women appears paltry (see table 1). Never the less, it is reassuring that almost 80% of the 10’042 identifies events could be allocated to identified persons.

| Category | Number of events (name mentioned) |

| Named persons in Stühlingen (190 men & 46 women) | 7’538 |

| Designated functionaries, not otherwise identified | 14 |

| Residents of Endingen | 14 |

| Residents of Lengnau | 15 |

| Residents of Gailingen | 29 |

| Residents of Tiengen | 108 |

| Residents of Randegg | 41 |

| Foreign Jews | 70 |

| Unresolved events | 2’211 |

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 Table 1. Allocation of events.

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 The method employed resulted both in high redundancy and blind spots. Women, children, and other dependents remain largely invisible. Rabbis, cantors, teachers, and ritual slaughterers were rarely covered by a protection list and were captured in this study only if people engaged in business or fell afoul of the law. Family names started to appear in 1649 for Weil/Weyl, 1662 for Meyer, 1679 for Gugenum/Gugenheimb, 1680 for Bickert/Pickert, 1692 for Bloch/Blokh, and 1704 for Bernheimb. These names could then be assigned retrospectively to patrilineal ancestors and their other descendants in turn. For thirty-six out of the 190 individuals no family name could be identified.

Comments

0 Comments on the whole Page

Login to leave a comment on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 7