⇑ 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 Page 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 ⇓

8-9

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0

¶ 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0

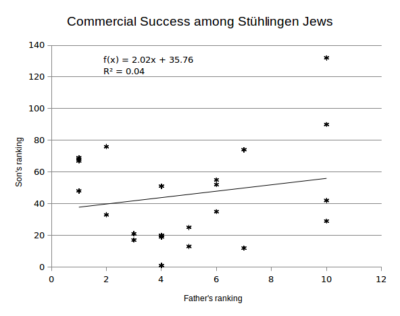

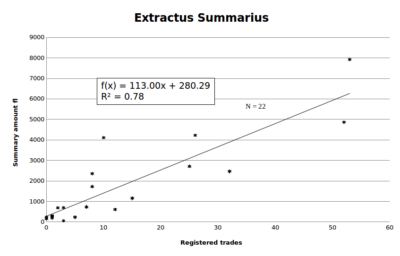

Figure 10. Commercial Success among Stühlingen Jews.

Figure 10. Commercial Success among Stühlingen Jews.

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 Could there be alternative explanations for these findings? Successful people, possibly, had more available capital. But this hypothesis can be shot down easily. One would then have to expect that the sons of successful traders would have to be successful too, because they were more likely to own inherited capital. When we compare the ranking in accumulated claims between fathers and sons (fig. 11), we see no signifcant correlation. In other words, sons of successful fathers do not seem to be more successful than those from poorer families. It is therefore unlikely that inherited wealth was responsible for commercial success.

¶ 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0

Figure 12. Total credit entitlements of 22 Jewish merchants (1739) by trade count.

Figure 12. Total credit entitlements of 22 Jewish merchants (1739) by trade count.

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 In 1738 Prince Joseph Wilhelm Ernst von Fürstenberg ordered that a summary of outstanding debts (claims) to the Jews be compiled in preparation for their planned eviction. The officials went to work and by April 25, 1739 produced a beautifully crafted document entitled Extractus summarius (see fig. 14, chap. 12, page 126),36 which listed the total credit entitlements of the twenty-two Jewish merchants active at that time. Every single one of the listed Jews is identifiable, and his major commercial activities have been recorded. No sales have been recorded for only three of the twenty-two. One was a young son (W1.3.4) in partnership with his father (W1.3), and the sales may have been listed in the latter’s name. Two others, (G1.2.2.3.1) and (C2.1.4.2.4), had paid their protection tax for several years, their outstanding credits were minimal, but they never recorded any sales. It is likely that they plied the peddling trade,37 and their individual transactions did not reach a level at which they had to be recorded. Thus it is possible to compare total sales with credit earned (fig. 12).

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 Figure 12 again shows a statistically highly significant association between the number of sales enacted and the total amount of claims due. In other words, the amount of money owed to a Jewish merchant was directly proportional to the number of his sales. It appears that the Jews listed in the Extractus summarius were neither moneylenders nor merchants; instead they plied an integrated business, with their claims being nothing else than accounts due. The comment accompanying the document, describing the reason for the magnitude of credits as:

“the vicious, double-dealing and fraudulent purchase, barter, credit, and other contracts against the poor inhabitants who had to seek the assistance of the Jews out of necessity and poverty,”38

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 amply illustrates the attitude of the princely house and its administration. But the governor’s (Obervogt) verdict granting the population sixteen years to the repay the loans presents a strong argument that the credit system provided by Stühlingen’s Jews constituted a significant component of market capitalization in the local economy.

36FFA, Judenakte, Politica, div. 1, subdiv. 2, “Extractus summarius,” April 25, 1739.

37Fontaine, “History of Pedlars in Europe.” pp. 8 – 34

38Rosenthal, “Heimatgeschichte der badischen Juden,” 180.

Comments

0 Comments on the whole Page

Login to leave a comment on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 7

0 Comments on paragraph 8

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 8

0 Comments on paragraph 9

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 9

0 Comments on paragraph 10

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 10

0 Comments on paragraph 11

Login to leave a comment on paragraph 11